Bridge increases access and quality of Kenyan nurseries and primary schools

While primary education has been theoretically free and compulsory since 2003 in Kenya (Article 53 of the Kenyan Constitution) many children do not experience this reality.

Since 2003, enrolment in Kenyan primary schools has steadily grown to 84% but in some regions, particularly in rural and slum communities, this figure is as low as 19%. However, of those lucky enough to be at school, many will not be learning as only an estimated 40% of Kenyan teachers have obtained the minimum knowledge required to teach (GEM: 2017)

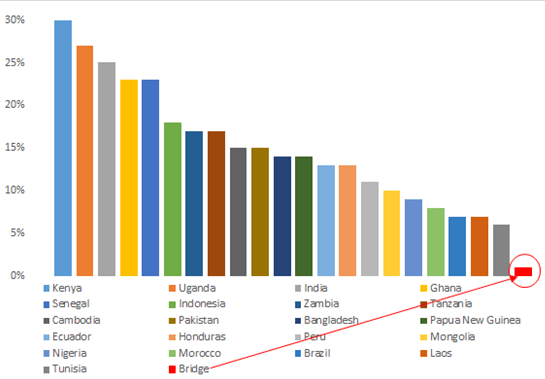

This is despite Kenya spending 28% of its national budget on education. Critics have argued the rapid expansion of free primary education may have improved access but not the quality of education. Furthermore, public schools are often far from ‘free’ with those parents of children who attend them often expected to pay hidden costs and fees.

Because of this, many parents have sought out affordable schools that emphasise value, quality, and accountability — some of these alternative providers even cost less than public schools.

In recent weeks, Class 8 pupils from across Kenya sat their primary school leavers exam – the Kenyan Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE); this includes thousands of Bridge pupils. The KCPE is a very significant moment for any Kenyan child, as it rounds off eight years of their primary education; for many, this is all the education they will receive. Few achieve even this. Passing your KCPE is one of two factors which determine if you can attend secondary school, the other being if you can afford it. Pupils have just one chance to perform to the required standard in their KCPE exam and with no supplementary assessments or coursework, it all hinges on one set of exams. The exam exerts incredible influence on their life chances.

There are plenty of reasons to be optimistic about the 2017 KCPE results; a security focus around exam papers and a new, data-driven indexing system that will provide each student with a unique personal identifier (UPI) are expected to help the process run smoothly. In parallel, there has been a continuation of the trend of increased KCPE registrations as more pupils pass through the education system. This year saw a 6.5% increase in registrations nationally, with more than 60,000 additional students sitting the exam compared to 2016. With the Global Learning Crisis at the front of everybody’s minds, this is a triumphant statistic, as more KCPE registrations mean more children in school, and more children leaving school with a primary education, right? If only it was that simple….

Whilst UNESCO has acknowledged the significant improvements made in terms of access to primary education in sub-Saharan Africa, statistics like these reveal a more complex problem. Access to education alone is not the only barrier to learning in Kenya, but access to quality education. As the recent World Bank Education Report highlighted ‘schooling is not the same as learning’. Parents are choosing schools where they believe their children will learn and where they believe they have the chance to succeed. For many parents, this means they are not choosing public schools. Rampant teacher absenteeism combined with low levels of teacher literacy, poor learner materials and overcrowded class sizes, are impacting on learning outcomes in Kenya in a big way.

The World Bank issued a working paper in January 2017 with the aim of understanding the standards of primary education across multiple African nations, including Kenya. The paper focused on three aspects central to learning outcomes:

- How much time do teachers spend teaching?;

- Do the teachers understand the subject they are teaching?; and,

- Do they know how to teach?

Their conclusions for all three are revealing.

The report found that in Kenyan primary schools specifically, there was a 15% chance that the teacher would be absent from the school and the pupils would spend the day in an ‘orphaned’ classroom. Although some other countries in the study had much higher absence rates, Kenyan primary schools also had a 48% chance that the teacher would be present in the school but would be absent from the classroom. When the likelihood that a teacher would be in school, in the classroom and still not teaching was taken into account students were receiving two hours and thirty-one minutes of tuition per day – under half the amount they should be receiving.

When presented with these figures it is plain that access to education is not the only problem in Kenya. An alternative to poor quality education is essential. The World Bank highlighted that in the face of such low standards of primary education many families are turning to affordable alternatives, where they are finding a better quality education with evidenced learning gains. Plus, in some cases, lower costs than “free” state schools after additional payments are considered.

Bridge is the largest provider of such alternative schools across sub-Saharan Africa and its pupils consistently score above the national average in their KCPE exams. Importantly, Bridge utilises technology to enhance the performance of both students and teachers and boasts a teacher absenteeism rate of close to 0% (see below).

This model has been yielding results; in the 2015 KCPE Bridge pupils scored a 63% pass rate compared to the national pass rate of 49%. This trend continued into the 2016 KCPE examinations, where Bridge pupils achieved a pass rate 10% above the national average. The 2017 results are anticipated to confirm the learning outcomes delivered by Bridge.

It is not only in affordable Kenyan APBET schools that the model has proven effective, Bridge has shown that it can replicate these learning gains in public schools too. In 2016 Bridge was chosen as the largest contributor to the Partnership Schools for Liberia (PSL) programme. An independent evaluation by CGD shows the model is delivering learning gains and other African governments are watching with interest. The PSL programme has demonstrated the potential benefits of operating PPP schools in sub-Saharan Africa, leveraging the expertise of private providers to deliver better outcomes whilst enabling the state to retain oversight and policy control.

As the country awaits the 2017 KCPE results, Kenya may be one of the countries looking to the PSL programme for inspiration. Emulating this model could enable Kenya to increase not only the number of KCPE examination registrations each year, but increase the number of pupils that pass and leave primary school with a bright future ahead of them.

Read more about our results in Kenya here.